lobsters

/CT Mirror:

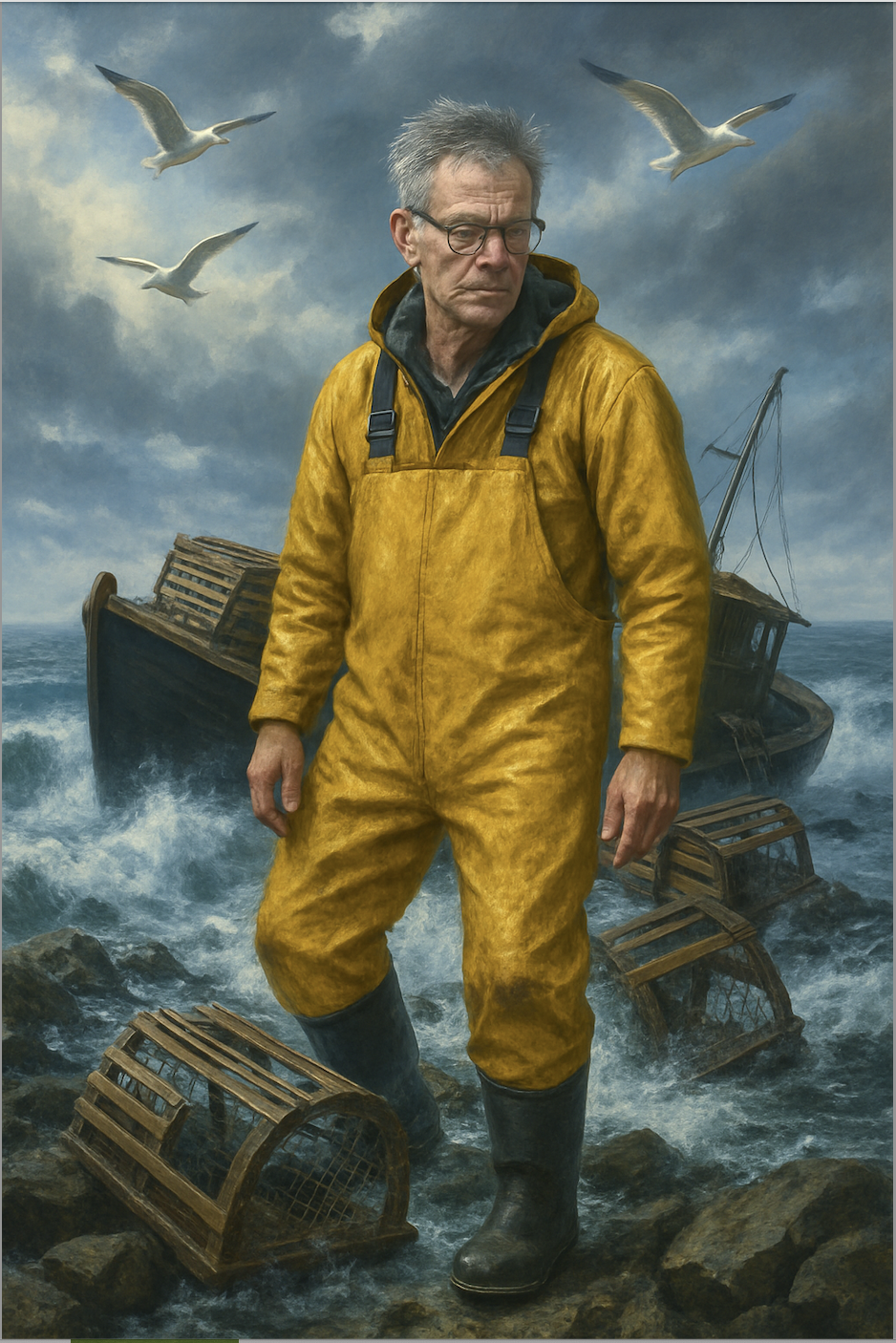

26 years after lobster die-off, CT lobstermen reflect on a net loss

The Long Island Sound lobster industry was decimated in 1999, but CT’s last few commercial lobstermen keep the tradition alive in Stonington.

Bart Mansi used to haul a thousand pounds of lobster a day. Now he sets out just a couple dozen traps, out of curiosity — or force of habit — and he’s lucky to catch 10 lobsters.

“I’ve been doing it all my life. I gotta see for myself,” he said. “But as far as trying to make a living, you can’t do it, not any more.”

Mansi converted his lobster wholesale facility on the dock in Guilford into a restaurant in the early 2000s. In the upstairs office on a sunny September morning, there are a few reminders of the life he used to lead: a “Captain’s Quarters” sign, framed photos from his lobstering heyday, the mast of his son’s fishing boat swaying gently out the window.

His eyes lit up as he recalled the good days. “We saw a lot of lobsters, a real lot of lobsters,” Mansi said.

In the 1980s and ’90s, Mansi was making a killing, along with the roughly 1,200 commercial lobstermen on Long Island Sound. The Sound was the third most-productive lobster fishery in the country, with 10 million pounds of lobster landings at its peak in 1998, including 3.8 million pounds in Connecticut.

But in the fall of 1999, lobstermen pulled up traps filled with limp, sickly lobsters, and soon after, hardly any lobsters at all. It was an unprecedented mortality event, and the lobster population never recovered. Connecticut saw only 181,000 pounds of lobster landings in 2024, less than 5% of the 1998 peak. Now most seafood restaurants in the state — including Mansi’s — import lobster from Maine or Canada.

The catastrophic die-off is still an emotional subject for Mansi and so many former lobstermen. In addition to the painful memory of losing their livelihoods practically overnight, resentment lingers about how it happened. The scientific consensus is that warming waters, and an epidemic of a crustacean disease called paramoebiasis, were the primary culprits — and that pesticides used to combat West Nile virus may have had an additional effect.

An occasional look at Connecticut’s remarkable people, places and things

But the catastrophe was complex and unprecedented, and not all scientists agree on which factors were the most significant. The lobstermen almost unanimously blame the pesticides, and they feel betrayed by the chemical manufacturers, the marine scientists, and the government — whose tightening regulations they resented and whose financial assistance they found inadequate.

In the early 2000s, as they fought for accountability and answers, the lobstermen had no choice but to adapt to the new reality. Some switched to fishing, clamming or catching conch, but most sold their boats and left the fishing docks behind entirely.

Now there are no full-time commercial lobstermen left in Connecticut.

Back in the 90s a friend of mine had lobster “hobby licenses” that permitted us to run ten traps apiece, and for many fished the waters off the RYC from March through late September, with enough success that I grew so tired of eating the crustaceans that to this day I won’t touch a lobster roll or, god forbid, a boiled one.

The summer of ‘99 saw an outbreak of mosquito-borne Nile Fever, and a great panic descended on the land. Health authorities in New York and Connecticut announced their intention to dump the pesticide methoprene into every storm drain to kill the mosquitos and more importantly, show that they were “doing something”. There was debate at the time whether this was wise, and I followed it because the debate centered around the effect on lobsters that methoprene might have. I distinctly remember a biologist from either Yale or UConn warning that lobsters and mosquitoes had the same basic exoskeleton, and what harmed one would also be fatal to the other.

The scientist’s warning was ignored, the methoprene was dumped into storm drains, the rains came and fushed the drains into Long Island Sound and, a week later? Two?, lobstermen, including hobbyists like my friend and I, went out one day and found nothing but dead lobsters in our traps and after a few days, nothing, dead or alive.

We pulled our traps, stacked them ashore and waited for better days; twenty-six years later, we’re still waiting. The effect on amateurs like myself was negligible: ten now-useless traps at $40 per; but as the CT Mirror article reports, it wiped out the commercial fishermen. I was representing Greenwich’s local lobstermen, ten in all, at the time, and they experienced the same disaster: lobsters one day, complete wipeout the next. I believe Gus Bertolf and his son continued to try to make a living fishing out of Cos Cob Harbor, but the rest quit within a month, and went on to find other occupations. My friend Bill Fossum became a real estate salesman, and, having gone out with him on his own boat many times and later joining him in the selling houses to strangers racket, I can say with certainty that the career change could not have been an improvement.

The “experts” still deny that there was a connection between flooding the Sound with methoprene and the subsequent overnight die off of every lobster in the water, but experts will do anything, say anything to protect their reputation. Suppose, for instance, every citizen in one state were ordered to be injected with a vaccine against a new disease. If, five days after receiving the injection, every single living person in that state were to die, would you accept the health authorities’ assurance that there was absolutely no connection, that the deaths were due to, say, global warming?

Or let’s suppose there was one laboratory in the world experimenting with creating a new, deadly form of virus, and one day people all around that laboratory became infected with and died from that virus. Would you believe and accept the official governmental assurances promulgated by UN health authorities, the dictatorship hosting that laboratory, and the top health bureaucrats of the United States that the two were unrelated and the appearance of the disease just outside the walls of the laboratory was mere coincidence?

Neither would I.

Here’s a Google treatment of the lobster die-off; it did not specifically address the question I asked concerning the identity of the biologist who’d predicted disaster in 1999, before the poison was employed, but does discuss the fatal effect methoprene. Of course, with Google, omission of a fact is by no means proof that something didn’t happen.

AI Overview

Yes, University of Connecticut (UConn) researchers confirmed in 2003 that the mosquito-control pesticide methoprene is deadly to lobsters at very low concentrations, leading to warnings against its use in storm drains that lead to Long Island Sound. UConn's research showed the pesticide could kill lobsters at 33 parts per billion, and a later 2010 study identified other chemicals from plastics and detergents that may have also contributed to lobster deaths, note UConn Today and CTPost. In response, state representatives, including those from UConn, supported a 2013 law prohibiting the use of methoprene in storm drains in Connecticut's coastal areas to protect lobsters, say Beyond Pesticides and CTPost.

Pesticide research:

UConn research in 2003 found that the pesticide methoprene could kill lobsters at a concentration of only 33 parts per billion.

Connection to lobster deaths:

The lobster industry seized on these findings to argue that methoprene was responsible for widespread lobster deaths in Long Island Sound, note Beyond Pesticides and CTPost.

Other contributing factors:

A 2010 UConn study led by Hans Laufer identified that chemicals from plastics and detergents may also contribute to lobster shell disease, a major cause of death, note UConn Today and CTPost.

Legislation:

As a result of this research and advocacy, Connecticut passed a law in 2013 prohibiting the application of methoprene in storm drains within coastal areas to prevent it from entering Long Island Sound, supported by a UConn professor, say Beyond Pesticides and CTPost.